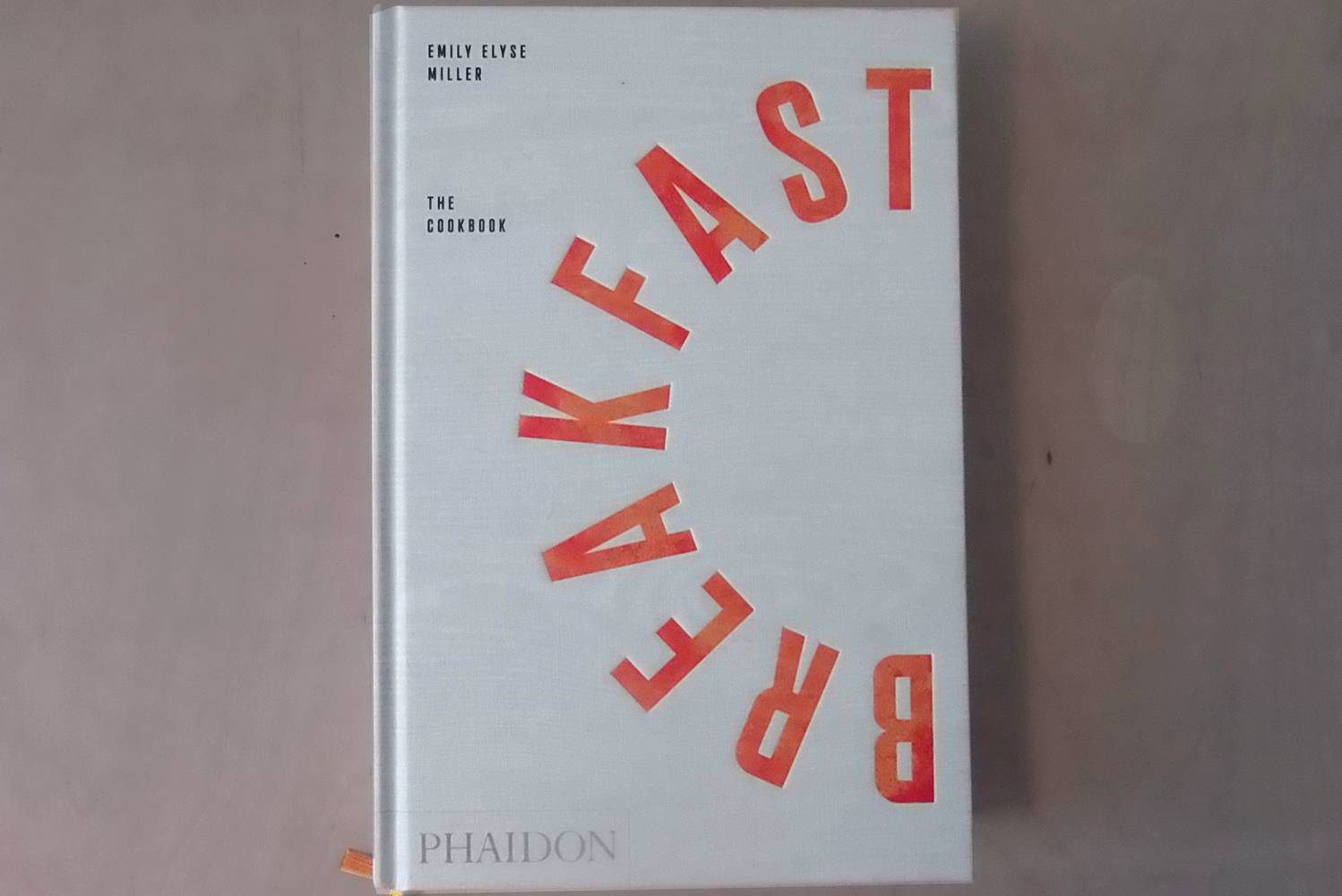

Do you know your Chinese Cruller from your Dutch Baby? Tell apart your Scrapple and your Hoppers? Billed as ‘the most important meal of the day’, breakfast can at once be nourishing, a vital and balanced fuel injection or a pure, indulgent comfort blanket. Leading authority on the way people around the world start their day in the kitchen, at the table or on the run, New York-based author, Emily Elyse Miller has provided hungry readers with what appears to be the definitive compendium on breakfast. That includes your Scrapple, Hoppers and everything else in between.

As the 484-page, hardback brick of paper lands on the kitchen table, confusion as to whether our humble morning meal warrants such a tome soon gives way to confusion as to why the world had to wait so long for it to be written.

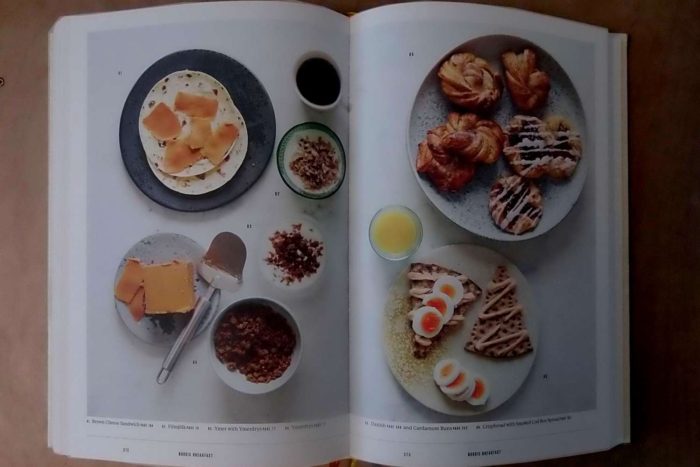

Spanning the continents, from the wildly diverse offerings of Europe alone, to Russia, South Asia, the Far East, Africa, the United States and onwards, the idea that breakfast could ever be recognisable to a person from the northern hemisphere as the southern quickly emerges as pure folly. Where Scandinavia, Europe and North America can lay their hands on a cinnamon swirl, something with an egg as the star or a chewy bagel and understand it counts as breakfast, what is perhaps most thrilling about Miller’s bible is the pancakes, the curries, the noodle dishes and soups that dominate Japanese, Taiwanese, South American and Malaysian breakfasts, the likes of which only intrepid travellers will have encountered before opening the pages of this Phaidon-published book.

What breakfast book would be complete without featuring the classic, Western European breakfast baked of croissants and brioche, cinnamon buns and Danish pastries?

The way that food has travelled with people and localised forms of various dishes have gone from the treasure of purists to be claimed wholesale by new populations is also, perhaps poignantly, stark as the pages pass. Lox, a US-version of cured salmon, the descendant of the famed gravlax, being just one example. That a book encourages you to cure your own salmon, as well as cure your own bacon and bake your own corn flakes lays bare the playful, ‘why not?’ attitude of the author. Miller opens up new culinary experiences from the seemingly mundane, while also elevating the mundane to cuisine of a culturally-important standing, like giving forensic direction to the assembly of the fatty and famed, Full English Breakfast.

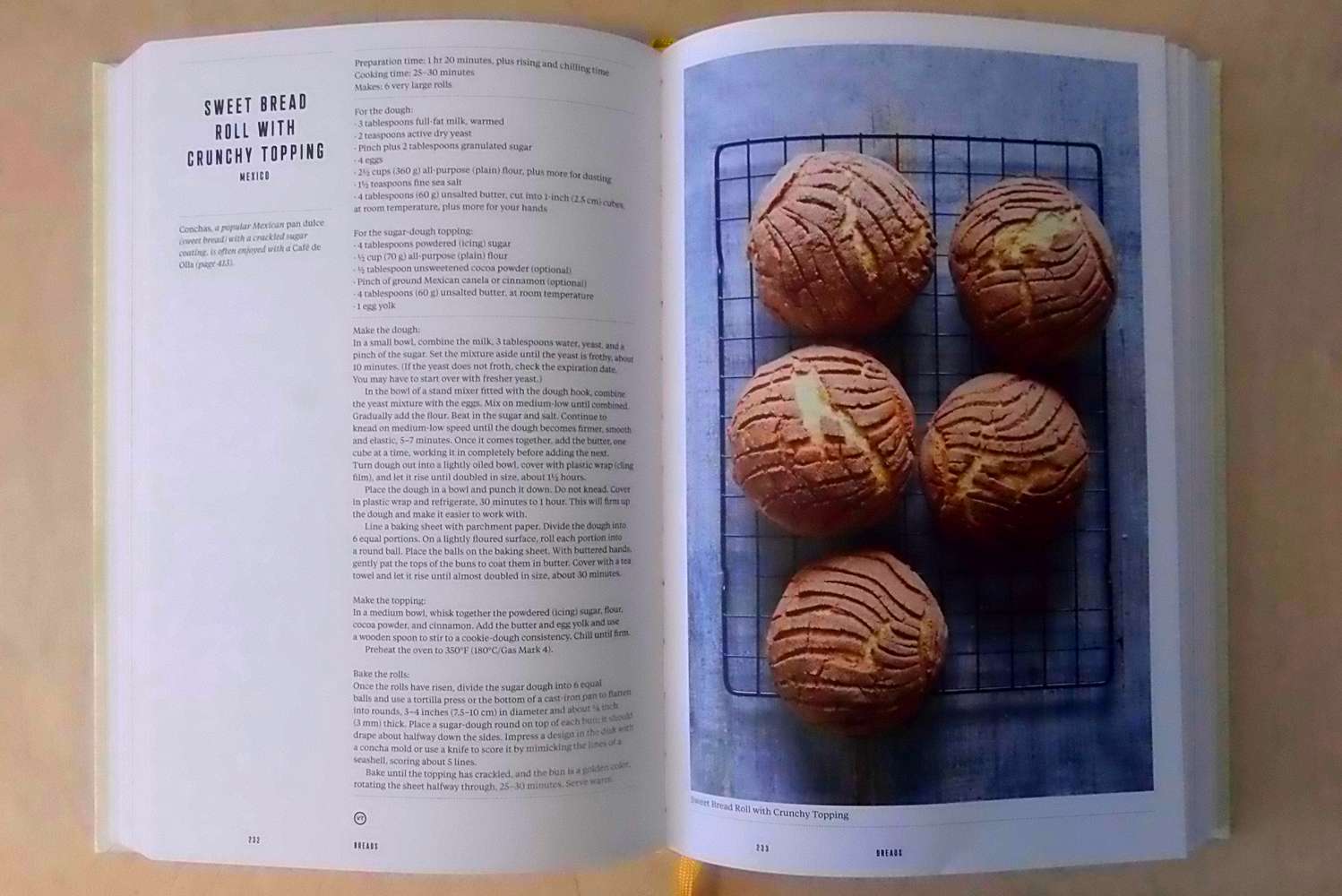

Amidst the sledgehammer message that the world is still a wondrously huge place when it comes to customs and tastes is, of course, a healthy diversity in traditional, international bakes. What breakfast book would be complete without featuring the classic, Western European breakfast bakes of croissants and brioche, cinnamon buns and Danish pastries? Of course, they’re all in the book, alongside variations on the theme from Italy and Argentina, right next to a section devoted entirely to breakfast cakes emerging from as far afield as Australia (banana bread) and China (turnip cake). In a chapter where bread is the star, filling steamed buns and sweet rolls (Filipino Pandesan looking exceptionally simple and tempting) sit side-by-side with unusual flatbreads and Buttermilk Biscuits.

To take on Breakfast: The Cookbook is to start a lifetime of adventure, such as that taken by the author. There’s simply no way to deal with it quickly, successfully and satisfyingly, whilst also giving every recipe the respect it deserves. With so many wild and wonderful ingredients to find for the more adventurous recipes, testing just a few of the bakes (and fries) in the book meant sticking to more familiar terrain to get a true feel of where the rest of Breakfast could take us. Pairing some of these with the jams, spreads and traditional breakfast drinks featured in the book is the logical next step.

Yeast Donuts

L-R: Without an illustration of the Yeast Donut in Miller’s book, the test baker has to keep the faith that what emerges from the bubbling oil is what the author intended.

In the ‘Stuffed and Fried’ section of Millers book there are two versions of donuts: the yeast variety that the world knows and loves and the, perhaps lesser-known cake donut. Whilst frying rings of cake sounds unquestionably appealing, not only for the fact it’s fried cake, but the lack of rising time in the preparation, the Dough Culture test bake took the old classic for a spin. Like many classic recipes, Miller gives an indication of ‘what could be’ in her simple descriptions, suggesting that these basic outlines can easily be given bold new flavours once the basics have been mastered. Of course, the donut is exactly that, a blank canvas. Her yeasted donut recipe is very basic, taking a simple enough mix of warm, enriched dough, ready to rise quickly (the 2 hour rising time is generous!) and the process divided between the customary two periods of shaping and resting. Where some bakers aim for the exemplary with defined frying temperatures and perhaps more attention to dough hydration, Miller’s recipe gets functional, passable donuts out of the fryer with minimal fuss. The results are equal to that attention to detail, with a batch of at least 8 fresh, ring donuts all yours for no great hardship.

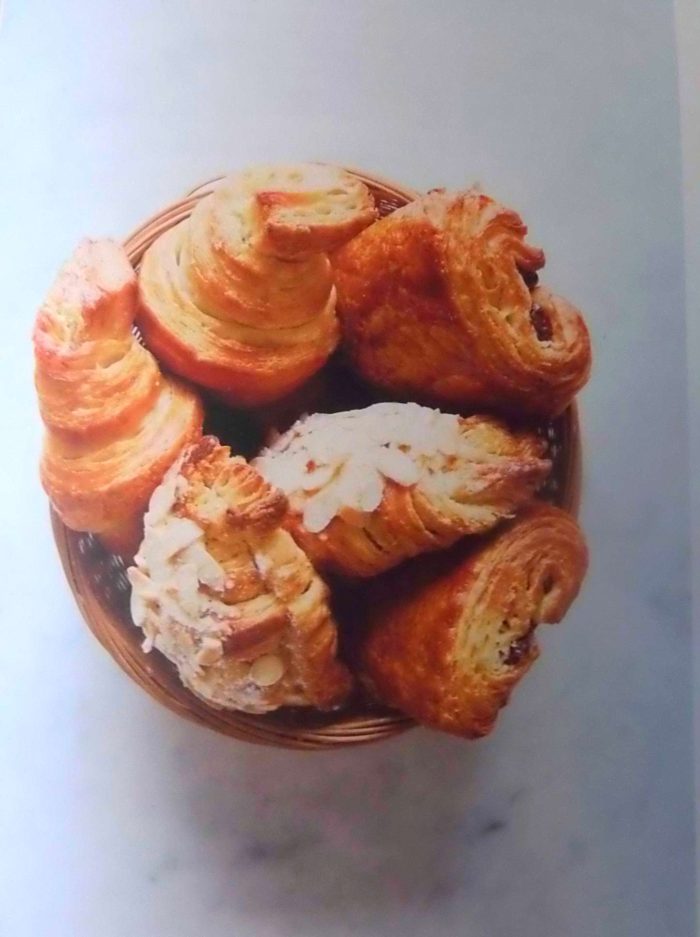

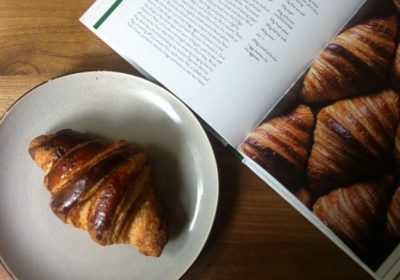

Pain au Chocolat

L-R: Somewhere in the enticing clutch of croissants and pastries is what the Pain au Chocolat should look like. The results of the test bake were more than encouraging, looking and tasting of professional standard.

The fun of laminating a croissant dough really only proves to be fun when it works. Thankfully, Miller’s attention to detail and her guiding, descriptive copy holds true in this instance and, with the care and attention everyone knows needs to be gifted to the croissant-making process, there’s no reason why her recipe for Pain au Chocolat should fail. No corners are obviously cut in this instance, where there is slight evidence of that in other parts of the book. These instances of simplification appear, commendably, to be for the sake of accessibility. The five instances of folding and the meticulous preparation of the flattened butter ‘package’, the intermittent cooling and rolling are present as the unavoidable stages in creating a croissant dough and the result is a fine, classic pastry. Instagram is awash with Pain au Chocolat that are taking on lives of their own, replete with cavernous air pockets, impossibly light golden skin and appearing to be the size of toddler’s heads. Miller’s are as we might recall them from Parisian counter tops – compact, shiny and chocolatey – and that’s an outcome to boost any home baker’s confidence.

Brioche

L-R: It sat…and sat…and sat…with nothing happening, but once the brioche hit the hot oven it detonated. The perfect version looking pretty, the test bake not a bad approximation.

The experience of an enriched dough hiding its rising potential isn’t altogether new, so for Miller’s brioche recipe to extol familiar virtues was not altogether unexpected. Initially really too wet to work with – the size of the 3 eggs that should be used aren’t accurately suggested – adding some extra flour was, sadly, unavoidable. Working faithfully through the instructions, chilling and flattening the rich, buttery dough, the rise was reticent to put it mildly. Yet, there were signs of life, which meant that introducing the lazy, unwilling loaf to the oven, after an extended rest, was justified as an educated gamble. Then, as with previous test bakes of classic, French loaves, came the explosion and a delicate brioche became a raging, tearing-at-the-seams monster. At 200°C for 15 minutes, down to 180°C for 25 more, for a diminutive loaf sitting in a mere 23 x 13 x 6.5 pan, proved too hot, yet not all ovens are created equal. To approach with caution can be the only sensible advice in the preparation, although the outcome in the form of delicately sweet and rich slices of decadent bread was worth the rollercoaster of adjusted temperatures and rising times.

Pastel de nata

L-R: File under ‘could have gone better’. The look of the tarts are all right, but what lies beneath lacks the sweet delicacy of the real thing.

Taking a deep breath, the famed Portuguese custard tart doesn’t look like an easy recipe to master quickly. For all the ease with which the bakers of Lisbon appear to churn these brilliant little tarts out, the signature swirly bottom as the layers of puff pastry are pushed out to form a pastry case never looks simple to achieve and the delicacy of a barely-baked, vanilla custard to go with it all too easily over or underdone. So, Miller’s recipe helps to fight the fear on one hand, going with a homemade ‘rough puff’ pastry instead of painstakingly layered, true puff pastry. Unlike other custard recipes, the Portuguese version demands a cinnamon-infused sugar syrup base to meet the egg yolk-emulsion at the next stage, which can easily confound a newcomer. The results of the bake are not quite as you’d expect from a café counter in Porto, the rough puff pastry, verging on shortcrust consistency (despite the swirl on the bottom), taking the edge off the usually crisp, shattering pastry case. The crazily high oven temperature of 260°C caramelised the tops too quickly as the custard ballooned in the heat and overcooked the vanilla cream filling without any effort. There’s a delicacy to Pastel de nata that just can’t be rushed or treated with short cuts and, unfortunately, the proof is right here in the hockey puck-like pudding.

Donut Holes and French Toast

L-R: There aren’t pictures in the book for Donut Holes or French Toast, perhaps because they’re easy to imagine and not so photogenic. But, both incredibly good and exceedingly bad for you.

Waste not, want not. To all intents and purposes, many of the best recipes – full stop – have emerged from waste, or indeed the avoidance of waste as resources proved themselves scarce in times gone by. In Breakfast, the traits of not discarding one single ounce of dough, if it can be helped, are evident in the frying of Donut Holes, yes the bits of dough cut from the middle of a ring doughnut. Simple enough, they puff up quickly into airy, little morsels that are then dusted with sugar (why not a little cinnamon?) and all too easily consumed while the rest of the mixing, rising, baking and frying is going on. A good use of brioche on days 2, 3 and 4 after baking, French Toast has always spoken for itself. Miller’s recipe, coming from the US, uses 3 whole eggs and finishes off with butter, icing sugar and maple syrup for a breakfast that brings on a rush of guilt before you’ve even put the first bite onto the fork… that’s if you think about it too much. It’s surely best to suspend belief and jump into something that is, and should be, a rare and indulgent treat.

Read On…

Breakfast: The Cookbook is published by Phaidon and is available now in hardback priced at £35 https://www.phaidon.com

Breakfast: The Cookbook is published by Phaidon and is available now in hardback priced at £35 https://www.phaidon.com